Kaza of Kharzan - Monasteries, churches and places of pilgrimage

Author: Tigran Martirosyan, 06/02/2024 (Last modified: 06/02/2024)

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the territory of the Sgherd (Siirt) sandjak (prefecture) of the vilayet (province) of Bitlis, of which Kharzan formed part as a kaza (county), was placed under the jurisdiction of the Sgherd Prelacy of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople. [1] In the years preceding the Armenian Genocide in 1915, archimandrite Paren Melkonian, in 1904, [2] and archimandrite Koryun Srapian, in 1908, [3] were the prelates of Sgherd. Until 1805, Sgherd was a bishopric under the jurisdiction of Surb Karapet (John the Baptist), the famous monastery in Moush, but afterwards it was decided to move the prelates and the clergy to the new seat at Sgherd (Siirt), the homonymous administrative center of the sandjak. From the second quarter of the nineteenth century and until 1865, the Sgherd Prelacy’s jurisdiction extended over Sgherd (the central kaza of the same name as the sandjak), Kharzan, and Shirvan, and included several counties in the adjoining prefectures beyond Sgherd. [4]

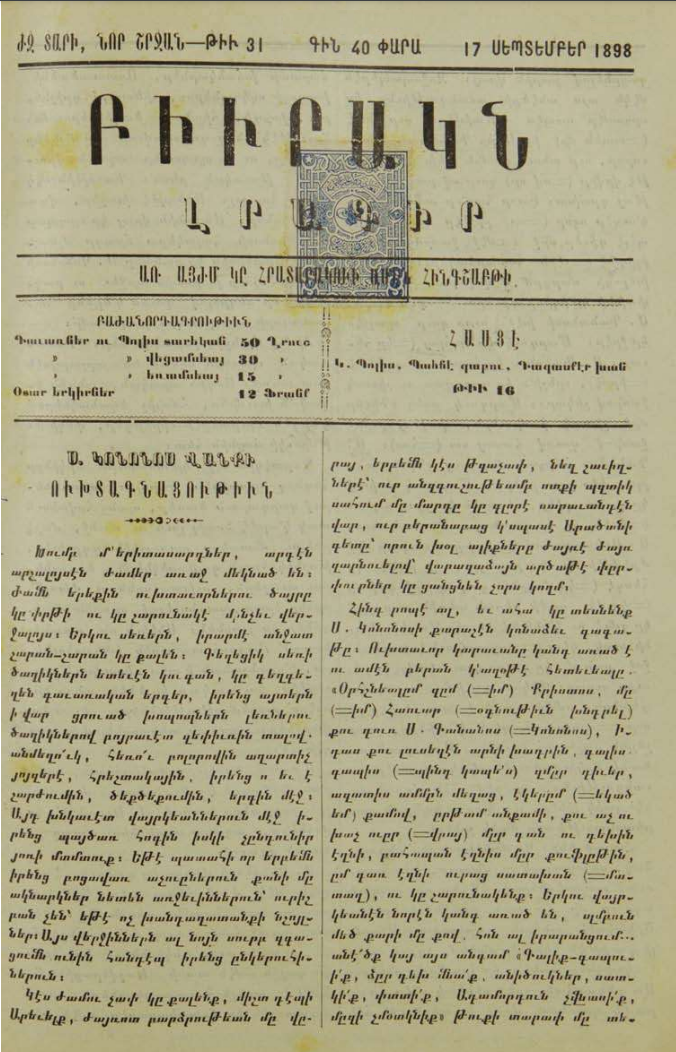

The 1904 Comprehensive Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital published in Constantinople, placed the number of Armenian churches in Sgherd at 32. [5] According to Archbishop Malachia Ormanian, an Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople, in the early 1900s there were 33 churches under the jurisdiction of the Sgherd Prelacy, which extended over Sgherd (the central homonymous kaza), Kharzan, Shirvan, and other counties within the Sgherd prefecture. The number of adherents to the Armenian Apostolic Church for the Sgherd sandjak was placed by Ormanian at 25,000, while Catholic Armenians, according to his estimates, totaled 500. [6] In 1900, an editorial in the newspaper Byurakn published in Constantinople, counted several Catholic churches in Sgherd, as well as 40-45 Protestant Armenian families in the prefecture, reportedly attending one preaching house. [7]

In the early medieval period, Arzn, the chief town of the Aghdzn gavar (county) of the Aghdznik ashkhar (province) of the Kingdom of Greater Armenia that gave name to Kharzan, was the seat of episcopacy under the jurisdiction of the bishopric of the Armenian Apostolic Church at Mtsbin, a historical city in the so-called “Armenian Mesopotamia” (present-day Mardin in southeastern Turkey). [8] Located on the bank of the Kharzana Get (Garzan Çayı) River, which flows south into Tigris, Arzn was long believed to have been one of the imperial capitals of Tigranakert founded in the first century BC by Armenian king Tigran II the Great. [9] The statistical report prepared by the Sgherd Prelacy in 1902 suggested that the largely Armenian populated village of Gerdashen was the site of the ancient town of Arzn. [10] A ruin of an unnamed church, which was built at a later time, had reportedly stood within the fortress walls of Arzn.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, according to the author of the article “Sgherd” published in 1900 in Byurakn, in almost each Armenian populated village throughout the sandjak of Sgherd, including those in Kharzan, the locals customarily had one church and one or more priests serving in a village. [11] This can be observed in the work of Armenian writer Teotoros Lapjinchian (Teodik) and the compilers of the 1902 statistics of the Sgherd Prelacy—all of whom reported, to the extent that they were aware, of course, a few dozen clergy serving in the monasteries and churches in several localities in Kharzan. [12]

The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report counted 1 monastery and 27 churches in Kharzan at the beginning of the twentieth century. A census carried out by the Patriarchate in 1913-1914, produced a figure for Armenian churches in Kharzan at 24 before the genocide. [13] The updated Patriarchate census data available to Kévorkian & Paboudjian, placed the number of monasteries in Kharzan in 1914 at 1 and churches at 25. [14] In his sole-authored work, Kévorkian (2012), who apparently upgraded the Patriarchate figures using supplementary census data available to him, identified 22 churches in Kharzan prior to 1915. [15]

The one monastery figuring in both the 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report and the 1913-1914 Patriarchate census was the Monastery of Saint Kononos (Surb Kononos). Because in the 1890s Kharzan, which was traditionally considered a part of Sassoun as attested by various primary sources used for this study, was transferred to Sgherd, while Hazzo (Kozluk), another traditional area of Sassoun with which in the High Middle Ages Kharzan formed the principality of Sassoun, [16] to Moush, the monastery is sometimes placed in Sassoun rather than in Sgherd. Famous for its prominence, the Surb Kononos monastery featured in “History of the Armenians” (in Armenian, Patmutyoun Hayoc) by a fifth-century Armenian chronicler Pavstos Buzand (Faustus of Byzantium), which described events from the military, socio-cultural, and political life of fourth-century Armenia.

The Surb Kononos monastery was located about 3 kilometers (2 miles) north-east of the village of Norshen (present-day Alıçlı), near 38°12'27.22"N, 41°31'29.41"E, in the valley of the middle reaches of the Kharzana Get River which, in that sector, was called Norshinadjour (Yanarsu Çayı) after the village. The village lay at the point of confluence of rivers Sghnout and Shat (Hazzoyi Get). [17] According to the 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report, in the past, the village population was almost entirely Armenian but, at the beginning of the twentieth century, only five or six Armenian households remained, while the number of Kurdish households grew to more than 100. [18] In the second half of the nineteenth century, the Surb Kononos monastery was the seat of episcopacy of the Armenian Apostolic Church. [19]

Holy Martyr Conon of Isauria (in Armenian, Kononos aysahalats or Konon Isavraci), to whom the monastery was dedicated, was born in the second century AD in Badin, a village near the Roman- and Byzantine-era town of Isauria (present-day Bozkır in Turkey’s Konya province), [20] whose inhabitants are believed to have received the Christian faith from the Apostle Paul. The Prayer of Kononos (in Armenian, Kononosi aghotyukn) was an Armenian incantation of protection against demons that was used to expel or bind demons in a manner similar to King Solomon’s signet ring. [21] Kononos was vested with powers to destroy the pagan shrines with the might of his word and make the demons dwelling in them obey and serve him. According to legend, in the area where the Surb Kononos monastery was erected, there was a large army of demons, who were filled into large clay jars, called karask in Armenian, interred, and sealed and closed until the Day of Judgment. [22] For the powers of Kononos in expelling the demons, subjugating them, and locking them in the karask, he earned the epithet “evil spirit-expeller” or “demon-expeller.” [23]

Among the locals, the Surb Kononos monastery was given the name Kananos or Yot dour Kononos, but to wider Armenian populations beyond Kharzan, the monastery was also known under the name of Surb Khach (Holy Cross) or Norshinavank, after the village the monastery stood close to. Throughout the eighteenth century, the monastery had an extensive diocese, covering 200 Armenian villages in Kharzan, Rndvan, Gurdilan (Kertulan, presently Kurtalan), and Hesnikif (present-day Hasankeyf). [24] By the early nineteenth century, the monastery reportedly retained the same number of villages as its possessions, which by that time were destroyed and rebuilt numerous times. [25] While by 1864, the above-mentioned areas were still concentrated in the possession of the monastery, the number of villages had decreased to 30 small localities, amounting to about 1,500 Armenian households. [26]

In the second half of the nineteenth century, having lost its former prominence and visibly dilapidated, Surb Kononos had become hierarchically subservient to the Gomac vank, one of the most prominent monasteries in Sassoun, otherwise known as the Monastery of Saint Peter the Apostle (in Armenian, Matin Arakelo vank), [27] located 23 kilometers (14 miles) north-east of Norshen. Writing in 1884, Manuel Mirakhorian, an Armenian school inspector who traveled extensively across Western Armenian provinces, admitted that in the past, the lands owned by the Surb Kononos monastery included more than 100 prosperous villages but, due to the Armenians’ internal migration or escape to safety, by the mid-1880s the monastic possessions were reduced to less than 20 villages. [28] According to the 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report, one such monastic possession was the village of Gergolek located in the Khrepan (present-day Yeniköprü) village group. [29]

This study relied on several primary sources which are listed below. Tadevos Hakobyan, Stepan Melik-Bakhshyan, and Hovhannes Barseghyan, the authors of the “Dictionary of Toponymy of Armenia and Adjacent Territories,” the travel guide published in 1884 by Manuel Mirakhorian, the 1904 and 1908 comprehensive calendars of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital in Constantinople, Raymond Kévorkian’s sole-authored treatise on the history of the Armenian Genocide published in 2012, and the newspaper Byurakn, provided additional data.

- The travel report by Aristakes Tevkants, an Armenian folklorist who journeyed to Western Armenia in 1878;

- The Statistical Report prepared by the Sgherd Prelacy in 1902;

- The 1913-1914 Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople census, including figures from supplementary Patriarchate census data available to Kévorkian & Paboudjian (1992);

- The book about the sufferings of the Armenian clergy during the genocide composed by Teodik in 1921; and

- The study on historico-geographical topography of Sassoun and Taron completed in 1947 by Vardan Petoyan, an eminent ethnographer and a native of the village of Gelieguzan in Sassoun, and published in 2005.

Below is a list of monasteries, churches, and places of pilgrimage in towns and villages throughout the kaza of Kharzan during the late Ottoman era. [30] Wherever possible, the list includes information regarding the number and known names of the serving clergy, which were extracted from Teodik’s brochure, the 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report, and the 1913-1914 Patriarchate census held at the Bibliothèque Nubar de l’UGAB in Paris. The current Turkified names and geographical coordinates of the towns and villages in Kharzan, where Armenian monasteries, churches, and places of pilgrimage were located, can be found in the article “Kaza of Kharzan—Demography”.

Monasteries of the Kharzan county

The Monastery of Saint Kononos (Surb Kononos)

Located in a mountainous, water-rich green area with fresh and clean air, the Surb Kononos monastery was believed to have been built in the ninth century AD. [31] Long known as one of the most renowned religious edifices in the area, the monastery fell into disrepair by 1900. [32] Built of stone, Surb Kononos, a large and splendid structure with a cone-shaped dome, gave visitors the impression of an oversized crib. The monastery’s yard, always cobbled and swept up, was surrounded by beautiful gardens. In the middle of the yard sprang a spring-well; its water was clear and cold. The stone walls of the church porch, a large and fine chamber, were decorated with elegant frescos and murals. The porch door led to the vestry, whose walls were also decorated with a few murals. The vestry had silver crosses and lamps that were lighted in front of the altar. On the altar, an “eternal flame” lantern made of earth was seen, in reverence of Saint Kononos. [33]

The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report indicated that the monastery was complete with three apses dedicated to Saint Shamuneh, Holy Mother of God Surb Astvatsatsin, and Saint Sargis. To the left of these vaulted apses there was a door that led to a sanctuary containing gravestones with inscriptions bearing the names of Saint Kononos’ father and mother. The monastery had a small and simple room for an abbot, called veharan in Armenian. There were also five or six two-storeyed rooms for the pilgrims. According to records made in a monastic record book, their construction year dated back to 1854.

In 1884, Mirakhorian observed that the monastery customarily had a priest or an abbot at all times. [34] However, G. Mouradian, the author of the article “Surb Kononos vanki oukhtagnacutiun” (Pilgrimage at the Monastery of Saint Kononos) published in Byurakn, noted with regret that if in the past the monastery was administered by more than one abbot, by the time of writing, in 1898, the administrative duties rested in the hands of one “helpless priest.” [35] The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report suggested that Father Arakel fulfilled the duties as the abbot of the monastery. In the years preceding the genocide, Father Nerses archimandrite Rshtouni assumed the abbotship. [36] Several laborers ministered to the monastic clergy. A few head of cattle were kept in the monastic barn to feed Kurdish gate keepers and Armenian laborers. [37] After the prayer service, the monastery’s holy vessels were handed over to a local Kurd āghā for storage, who acted as the grand sacristan (in Armenian, lusararapet). [38]

There was a specially designated place in the monastery where persons suffering from epilepsy, as well as the feeble-minded, were brought in “for healing.” A silver chain, thought to have been blessed by Saint Kononos himself, was wrapped around the neck of each of the sick men. It was believed that if the chain slipped off a person’s neck, the one who was wearing it would be healed. [39] After wearing the chain for a few days, the sick were thought to have taken their murad (translated from Arabic as something to be desired or wished for) and were released. In the southern corner area of the monastery there was a dirt mound, rising to a height of about one meter, which was said to have been the lair of the Chief of Devils (in Armenian, Satanayi petn) condemned to eternal imprisonment by Saint Kononos. [40]

The Saint Atovmianc (Surb Atovmianc) monastery

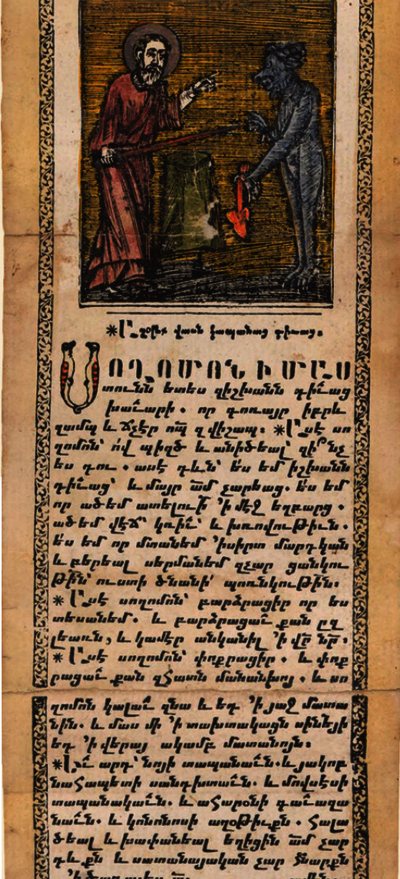

The monastery was situated to the east of Norshen, one or two kilometers (about one mile) south from the Surb Kononos monastery at the point of confluence of rivers Kharzana Get and Shat. Also called Atomianc monastery, and known to the locals by the name Kamatoun, the structure by the first half of the nineteenth century lay in ruins, desolate and empty. [41] During the High Medieval Period, the monastery was famous for housing a scriptorium, a writing room that was set aside for the use of scribes, typically monks themselves, engaged in storing and copying manuscripts. Several ancient manuscripts were preserved in the Surb Atovmianc monastery up until the genocide. The most famous one, directly associated with the monastery, was a Haismavourk handwritten by archimandrite Gagik in the ninth and tenth centuries. Ritual books Haismavourk were medieval Armenian collections of the feasts of the Lord and the lives and martyrdom of the saints. The one kept at the Surb Atovmianc monastery was called Atomagir after the monastery. [42]

The construction date of the monastery remains unknown. It is known, however, that the structure was built with hewn stones and comprised of a church and a chapel. There was a centuries-old monastic graveyard nearby. [43] According to archimandrite Hovhannes Aghtamarci, in 1869, a large remnant of the church still stood on a hillock to the north of the monastery. Judging by the size of this remnant, the church must have been quite impressive a structure, extending to about 28 footpaces in length, with each footpace consisting of one normal walking step, or approximately 0.75 meters (30 inches). A small chapel near the church was dedicated to the Atovmianc saints. It was believed that the chapel was the site where the saints “drained out their blood” and where they were laid to rest. [44]

The saints in question were two Armenian generals, Atovm Gnouni and Manachihr Rshtouni, who served in the army of Sassanid king Yazdegerd II. With Christianity gaining ground in the Persian Empire in the fifth century, Yazdegerd started persecution of Christians, forcing on them the worship of fire. [45] The generals, who preached boldly about Jesus Christ, had to flee to Armenia to escape persecution. According to tradition, once in Armenia they founded a nobility with residence in the village of Vochkharanc, [46] also spelled as Vochkhranc. After putting up a fierce resistance to the Persian army, the whole village population was slain. Executed by the Persians, the generals were believed to have been buried on a site where later the Surb Atovmianc monastery was built. As if to confirm this, the monastery was marked on the map drafted in 1691 by Armenian poet, printer, and historian Yeremia Kyomurdjian Kostandnupolseci under the name of “Vochkharanc monastery.” [47]

The Derakeri monastery

The monastery, whose name likely came from Assyrian word Dêrôkîro, meaning “Tree Resin monastery” (translated to Armenian as Khezhavank), stood on the top of a cliff rising steeply from a bank of the Kharzana Get River, near an ancient, half-ruined fortress called Kharzana berd in Armenian. The fortress stood close to the village of Zokh or Zok (present-day Yanarsu), the principal town of the kaza of Kharzan, which throughout most of the nineteenth century was largely populated by Armenians. In the years preceding the genocide, the remnants of the fortress walls were still present. According to a genocide survivor from Sgherd, the Derakeri monastery was a large structure perching atop the cliff like eagle’s wings. There was a mountain trail connecting the monastery with the ruins of the fortress town at Arzn. [48]

Aynkasr

A recent historico-demographic study suggests that there was a ruin of an unnamed Armenian monastery lying to the southeast of the village. [49]

Berah

Petoyan reported that the village housed an unnamed arched monastery. More recent research suggests that the name of the monastery was Tgha Manuk and that it was, in fact, a convent. [50] It should be pointed out here that in some Armenian folklore materials, Jesus Christ is figuring as Manuk Tgha, translated from Armenian as “Baby Boy.” [51] Hakobyan et al. concur that the locals called the village church “monastery.” [52]

Djoman

According to Petoyan, there was a ruined unnamed monastery in the village.

Kanikhouyl

According to Petoyan, the village, whose Armenian name Tsakaghbyur means “hole spring-well,” housed two unnamed dilapidated monasteries.

Churches of the Kharzan county

Aranz

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Aynkasr

The Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin). According to the 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report, at the beginning of the twentieth century the church was in ruins. There was a chapel of the same name near the church. One serving clergyman, Father Harutyun.

Barendj Verin and Barendj Nerkin

The Church of Holy Resurrection (Surb Harutyun). One serving clergyman, Father Psak Ter-Manoukian. The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report suggested that at the beginning of the twentieth century, the church was in ruins.

Barzan Verin and Barzan Nerkin

One unnamed church.

Berah

The Church of Saint Cyricus (Surb Kirakos). According to Teodik, one serving clergyman, Father Hovhannes Sargsian. The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report suggested that there was second serving clergyman, Father Manuel, and that at the beginning of the twentieth century, the church was in ruins. The 1913-1914 Patriarchate census counted two serving clergymen.

Beybou

One unnamed church.

Bimer

The Church of Saint John the Baptist (Surb Karapet). According to Teodik and the 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report, the church was in ruins. There was a chapel of the same name near the church. One serving clergyman, Father Sargis Ter-Honoyan. The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report mentioned two serving clergymen, Father Grigor and Father Manuel.

Bolend

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Djafan

The Church of Saint Elias (Surb Yeghia).

Djeldika

The Church of Saint John (Surb Hovhannes). The 1913-1914 Patriarchate census counted one serving clergyman. The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report suggested that at the beginning of the twentieth century, the church was in ruins. There was a chapel of the same name near the church.

Djemzarik

The Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin). The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report suggested that the church was a beautiful edifice.

Djoman

The Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin). One serving clergyman, Father Danan Sahakian.

Djouvayc

The Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin).

Dousatak

The Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin). One serving clergyman, Father Martiros Kassian.

Gerdashen

The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that at the beginning of the twentieth century, the unnamed church that stood within the fortress walls of the ancient town of Arzn near Gerdashen was in total ruins.

Gola masia

One unremarkable church, according to Mirakhorian. The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that at the beginning of the twentieth century the church was in ruins. Near the village, whose Armenian name Dzknalich and Kurdish name Golamasiya mean “fish lake,” there were ruins of an ancient Anoushirvan fortress, Turkified to Zercel Kale. [53]

Gyozaldara

One unnamed church. Two serving clergymen, Father Manouk and Father Grigor Ter-Hakobian.

Hadjr

One unnamed church.

Hadhadk

The Church of Saint George (Surb Gevorg). One serving clergyman, Father Gevorg Yeretsian.

Hashas

One unnamed church. According to Petoyan, the village had an arched and undamaged church.

Haznamer

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Hope

One unnamed church. One serving clergyman, Father Manuel.

Housseynik

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Kanikhouyl

One unnamed church.

Kelhonk

The Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin). The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that at the beginning of the twentieth century the church was in ruins.

Khnask

One unnamed church.

Khndouk

The Church of Saint George (Surb Gevorg). The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that at the beginning of the twentieth century, the church was half-ruined. The church, with the whole village, has likely been submerged beneath the waters of Tigris as a result of alterations of riverbanks caused by the construction of the Ilısu Dam.

Khoubin

The Church of Saint John (Surb Hovhannes). One serving clergyman, Father Abraham Ter-Tovmasian. The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report suggested that the name of the serving clergyman was Father Grigor and that beginning from 1895 the church was derelict and in ruins.

Khoulik

One unnamed church. One serving clergyman, Father Hovhannes Shahinian.

Khrepan

One unnamed church.

Marib

The Church of Saint George (Surb Gevorg). The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that at the beginning of the twentieth century, the church was in total ruins.

Marmarono

One unnamed church.

Melha

Tevkants reported the Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin).

Melikan

The Church of Saint George (Surb Gevorg).

Merke radjal

One unnamed church.

Mlafan

The Church of Saint George (Surb Gevorg). One serving clergyman, Father Khoren Grigorian. According to Petoyan, the church had arched ceilings, but was in ruins.

Nazdar

One unnamed church.

Norshen

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Paloni

Tevkants reported the Church of Saint Minias (Surb Minas). The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report mentioned the Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin) and that at the beginning of the twentieth century, the church was in ruins.

Pgheghik

One unnamed church.

Rndvan

The Church of Saint George (Surb Gevorg). One serving clergyman, Father Karapet Mouradian. The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report suggested that the church was a splendid edifice, and that the serving clergyman’s name was Father Grigor. This church is said to have supplied communion bread to the homonymous Church of Saint George (Surb Gevorg) at Marib. In the late 1880s, Rndvan had a total population of 210 households, of which 90 were Armenian Apostolic and 30 Armenian Protestant. According to the 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report, Surb Gevorg was an undamaged, splendid edifice. Mirakhorian, on the other hand, suggested that Surb Gevorg was a gloomy structure and that there were four serving clergymen representing the older priestly generation. Attached to Surb Gevorg there was another, partly open, church named after the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin), where worship services were held during the summertime.

In the early 1880s, the Ottoman authorities set their hands to do away with semi-autonomous lifestyle of Kharzan’s Yazidis and Armenians. First, the authorities designated a kaymakam, or district governor, in Rndvan, which served as the kaza’s administrative center. Then, in 1837, the Yazidi chieftain of Kharzan by the name of Mirza āghā, known also as Sheikh Mirza, was summoned to Diyarbakir, where the Turks cunningly killed him. Mirza’s guards were able to transfer the remains back to Rndvan, where they were interred. This outstanding individual was revered by both Yazidis and Armenians. Because Surb Gevorg was built during Mirza’s chieftainship, to which he had made some contributions, the Armenians inscribed his name on the frontal side of the church in gratitude. The inscription in Armenian read as follows: Mirza Yezitin i havitenakan hishatak (To the eternal memory of Mirza the Yazidi). [54]

Because in the late nineteenth century, Rndvan’s 800 households were inhabited by a large segment of Syriac population, living alongside with Armenians and Yazidis, the town housed a Syriac church called Mar Goris. [55]

Sbhi

The Church of Saint Sargis (Surb Sargis). The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that at the beginning of the twentieth century, the church was in ruins.

Soulan Nerkin

According to unconfirmed information, a dilapidated Armenian church stood in the village until the early twentieth century. [56] The church, with the whole village, has likely been submerged beneath the waters of Tigris as a result of alterations of riverbanks caused by the construction of the Ilısu Dam.

Taghari

One unnamed dilapidated church.

Tera

One unnamed church.

Vahset

The Church of Saint James (Surb Hakob). The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that at the beginning of the twentieth century, the church was half-ruined.

Zennaf

Tevkants reported the Church of Saint Minias (Surb Minas).

Zevik

One unnamed church. The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that at the beginning of the twentieth century, the church was in ruins.

Zokh

The 1904 Comprehensive Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital reported the Church of the Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin). However, Teodik identified the Church of Saint Sargis (Surb Sargis). One serving clergyman, Father Sargis Ter-Sargsian. The 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report noted that at the beginning of the twentieth century, the church was in ruins. According to Petoyan, the church was covered with planks․

Zvenk

One unnamed church.

Places of pilgrimage in the Kharzan county

Church at Saint Kononos monastery

The church, a cradle-like and gallant structure, [57] that formed a part of the monastic complex, until the mid-nineteenth century was a popular pilgrimage site. For Khachverats, or Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, festivities were held at the church, during which dances, joyful chants, exchange of gifts, and sacrificial offerings were arranged for some 3,000-4,000 pilgrims arriving from Kharzan, Sassoun, and more remote corners of the region. Divided into two groups, young Armenian males and females would start dancing in the monastic yard long before sunrise. [58] The site of the church was considered sacred not only by the Armenians, but also the Kurds, who would go there on a pilgrimage (see Tomb of Saint Kononos below).

This said, the 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report suggested that the gravesite of Sheikh Yomer (also spelled as Sheikh Amar or Sheikh Omar) found at the outer church porch and venerated by the Kurds during their pilgrimages, was fake. The report stated that “[falsification] was so typical to the Kurds,” [59] who called the Armenian monastic complex Dera Şex Âmîr, [60] translated from Kurdish as “Monastery of Sheikh Omar.” The report added that by 1895 the pilgrimage to Surb Kononos went on the decline because in the recent past many Armenian inhabitants of Norshen either gradually assimilated among the Kurds or had to flee the village, after which nomadic Kurdish tribes seized the opportunity and settled in it.

Cross of Christ’s wood piece at Saint Kononos monastery

A piece of the wood of which, so it was believed, the Cross of Jesus Christ was made, was kept at the monastery. In addition to the veneration of Saint Kononos, this holy relic made the monastery an important pilgrimage site.

Tomb of Saint Kononos at homonymous monastery

Near the monastery’s left-side entrance gate, against the church’s southern wall, there was the tomb of Saint Kononos. The tomb, which at the turn of the nineteenth century was in an unsightly state, attracted Armenian pilgrims from all corners of the region. The Kurds made their own pilgrimages there, calling the grave site the “Tomb of Sheikh Yomer.” Once at the site, they were assigned to a private area within the monastery for prayers. [61] A few Armenian primary sources indicated that Sheikh Yomer was the defender of the Surb Kononos monastery from attacks and intimidation by Kurd āghās and the marauding Kurdish tribes. In gratitude for his good deeds, the sheikh was buried at the site of the monastery. Before the genocide, the headstone bearing a commemorative inscription reportedly still stood on monastery grounds. [62]

Saint Atovmianc (Surb Atovmianc) monastery

Before the genocide, the monastery was a significant pilgrimage site not only for Armenians of Kharzan and the adjacent areas, but also for wider Armenian populations in the vilayet of Van. [63]

Chapel at Saint Atovmianc (Surb Atovmianc) monastery

A small chapel, known as Saint Atovmianc (Surb Atovmianc) or Surb Atovmá, stood near the monastery. The structure, which reached the beginning of the twentieth century in a half-ruined state, sat atop a hillock where, according to tradition, the remains of Atovm Gnouni and Manachihr Rshtouni were buried. Among the locals, and to the many villagers who went there on pilgrimages or for veneration, the chapel was known as a sacred site endowed with wonder-working powers, especially for barren women. [64]

Saint Elias (Surb Yeghia) church at Djafan

According to the 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report, the church was an important pilgrimage site believed to have been endued with miracle-working powers.

Ruins of unnamed church and fortress near Pgheghik

According to the 1902 Sgherd Prelacy’s statistical report, an unnamed church and the nearby fortress at Pgheghik (possibly Yapraklı nowadays) were places of pilgrimage. Pgheghik was situated at a fairly close distance from the walled fortress-town of Kale Sheikh Baj, called Keleya Şex Baj in the Kurdish language, which reportedly was still in existence in the early twentieth century. [65]

Chapel at Maruta Holy Mother of God (Surb Astvatsatsin) monastery

The chapel of the ruined Surb Astvatsatsin monastery, otherwise known as the Marutavank monastery, which perched atop Mount Maratuk (Turkified to Malato Dağ) in Sassoun, stood outside of Kharzan. However, the chapel is mentioned here because both the mountain and the site of the monastery were considered sacred by Kharzan villagers where they would go on a pilgrimage. In fact, Mount Maratuk was considered sacred not only by the Armenians, but also the Kurds. Hakobyan et al. place the chapel at Marutavank in Kharzan, near the Armenian populated village of Arvetoc or Arvoutouc (present-day Sarıyayla). [66] However, other authors consider the village as forming part of the Maratuk village group in Sassoun proper. [67]

The chapel at Marutavank was famous for its religious feasts and rituals, such as Vardavar (Transfiguration of Jesus Christ) and Astvatsatsin yev Surb Khach (Holy Mother of God and Holy Cross), which were customarily observed on Mount Maratuk at definite seasons of the year. [68] Subsequently, every year, Armenian villagers from Kharzan, as well as Hazzo-Khabldjoz, Motkan, Psank and other adjacent areas in Sassoun and Moush, traveled to the chapel to spend a few days on Mount Maratuk. The pilgrims would pour into the area in large crowds. During celebratory activities, they customarily made sacrificial offerings. Along with this, dances and chants were arranged both for the pilgrims and residents of the nearby villages in the Bulanik and Manazkert kazas. [69] On Vardavar and Surb Khach, holy mass was offered in the chapel. [70]

- [1] Mirakhorian, Manuel. Nkaragrakan oughevorutioun i hayabnak gavars Arevelian Tachkastani [A Descriptive Journey to Armenian-populated Regions of Eastern Turkey]. Constantinople: Partizpanian Publishing House, 1884, Vol. 1, p. 75.

- [2] 1904 Entardzak Oratsouyts S. Prkchian Hivandanoci Hayots [The 1904 Comprehensive Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital], Constantinople։ H. Matevosian Publishing House, p. 374.

- [3] 1908 Entardzak Oratsouyts S. Prkchian Hivandanoci Hayots [The 1908 Comprehensive Calendar of the Holy Savior Armenian Hospital], Constantinople։ H. Matevosian Publishing House, p. 249.

- [4] The 1908 Comprehensive Calendar of Holy Savior Hospital…, p. 315.

- [5] The 1904 Comprehensive Calendar of Holy Savior Hospital…, p. 375.

- [6] Ormanian, Malachia. Hayots Yekeghecin yev ir patmoutiune, vardapetoutiune, varchoutiune, barekargoutiune, araroghoutiune, grakanoutiune ou nerka kacoutiune [The Church of Armenia: Her History, Doctrine, Rule, Discipline, Liturgy, Literature, and Existing Condition]. Constantinople: V. & H. Ter-Nersessian Publishing House, 1911, pp. 261-262.

- [7] Byurakn, No. 19-20, May 16, 1900.

- [8] Ter-Minassiants, Yervand. Hayoc yekeghecu haraberutyunnere Asorioc yekeghecineri het [The Relations of the Armenian Church with Assyrian Churches]. Etchmiadzin: Mother See of the Armenian Apostolic Church Press, 1908, p. 162.

- [9] See, for example, Abovianc, Gevorg. Hamarotutyun Hayoc azgi patmoutean [A Concise History of the Armenian People]. Tiflis: M. Sharadze Publishing House, 1894, p. 8.

- [10] Statistical Report prepared by the Sgherd Prelacy in 1902, sheet 10.

- [11] Byurakn, No. 19-20, May 16, 1900.

- [12] Lapjinchian, Teotoros (Teodik). Koghkota Trqahye Hogevorakanoutyan yev ir Hotin Aghetali 1915 Tariin [The Calvary of Ottoman Armenian Clergy and its Flock’s Catastrophic Year of 1915]. Tehran: S.N., 2014, pp. 129-131; Statistical Report prepared by the Sgherd Prelacy, 1902, sheets 8-12.

- [13] The 1913-1914 Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople census. Paris: Bibliothèque Nubar de l’UGAB, pp. 65-68.

- [14] Kévorkian, Raymond, and Paul Paboudjian. Les Arméniens dans l’Empire Ottoman à la veille du genocide. Paris: ARHIS, 1992, p. 505.

- [15] Kévorkian, Raymond. The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London: A.R. Mowbray, 2012, p. 277.

- [16] Tomaschek, Wilhelm. Sasun und das Quellengebiet des Tigris [Sassoun and the Area around the Sources of the Tigris River], transl. by H. Barnabas V. Bilezikdjian, Vienna: Mekhitarist Press, 1896, p. 61.

- [17] Petoyan, Vardan. Sasuni yev Taroni patma-ashkharhagrakan teghagrutyune [The Historico-geographical Topography of Sassoun and Taron]. Yerevan: Lusakn, 2005, p. 54.

- [18] Statistical report prepared by the Sgherd Prelacy, 1902, sheets 10-11, No. 51 (Norshen).

- [19] Hakobyan, Tadevos, Stepan Melik-Bakhshyan, and Hovhannes Barseghyan. Hayastani ev harakits shrjanneri teghanounneri bararan [Dictionary of Toponymy of Armenia and Adjacent Territories], Vol. 3, Yerevan: Yerevan State University Press, 1986, p. 208.

- [20] Conon of Isauria should not be confused with Holy Martyr Conon the Gardener of Pamphylia, who lived in the third century AD.

- [21] Hmayil: Part 24, in Grabar yev Gini, accessed July 19, 2022, https://krapar.org/hmayil/hm1_24.html#fn5t.

- [22] Srvandztiants, Garegin. Yerker [Literary works], Vol. 1: Groc ou broc, Yerevan: Armenian SSR Academy of Sciences Press, 1978, p. 75.

- [23] Harutyunyan, Sargis. Hay hmayakan yev zhoghovrdakan aghotkner [Armenian Incantations and Folk Prayers]. Yerevan: Yerevan University Press, 2007, p. 347.

- [24] Badalyan Gegham. “Arevmtian Hayastani patmajoghovrdagrakan nkaragire Mets Yegherni nakhorein (mas VIII-rd)” [A Historico-demographic Description of Western Armenia on the Eve of the Armenian Genocide, Part VIII: Sassoun and the Town of Bitlis], Vem, No. 2 (58), 2017, p. 30․

- [25] Hakobyan et al., Dictionary of Toponymy of Armenia…, Vol. 3, p. 208.

- [26] Tigranian, Mkrtich. Hayeli gortsots Tigranean Mkrtich vardapeti yev aṛajnordi Kiurtistanu [Reflection of the Work of Mkrtich Tigranian, an Archimandrite and Spiritual Leader of Kurdistan]. Constantinople: Tadevos Dividjian Publishing House, 1864, p. 7.

- [27] Badalyan, A Historico-demographic Description of Western Armenia…, p. 30․

- [28] Mirakhorian, A Descriptive Journey to Armenian-populated Regions․․․, Vol. 1, p. 74.

- [29] Statistical report prepared by the Sgherd Prelacy in 1902, sheet 10, No. 50 (Khrepan).

- [30] Non-Armenian readers should be aware that, in this study, the letter Ց ց appearing in Armenian monastery and church names and transliterated into C c as, for example, in “Atovmianc monastery” or “Gomac vank,” should be pronounced as a Z sound, as in the German word Zeitung, and not as an S sound or a K sound, as in the English words.

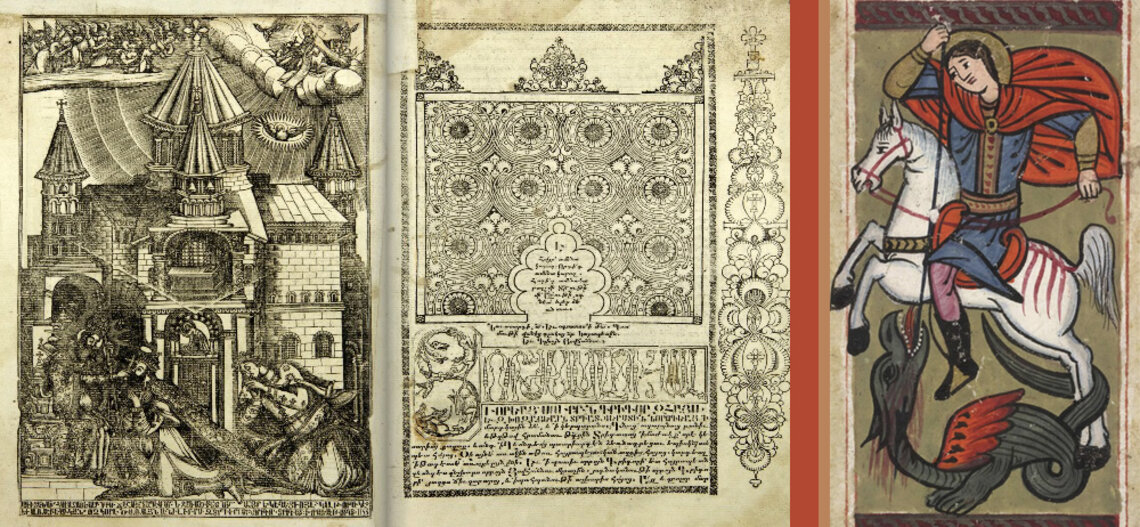

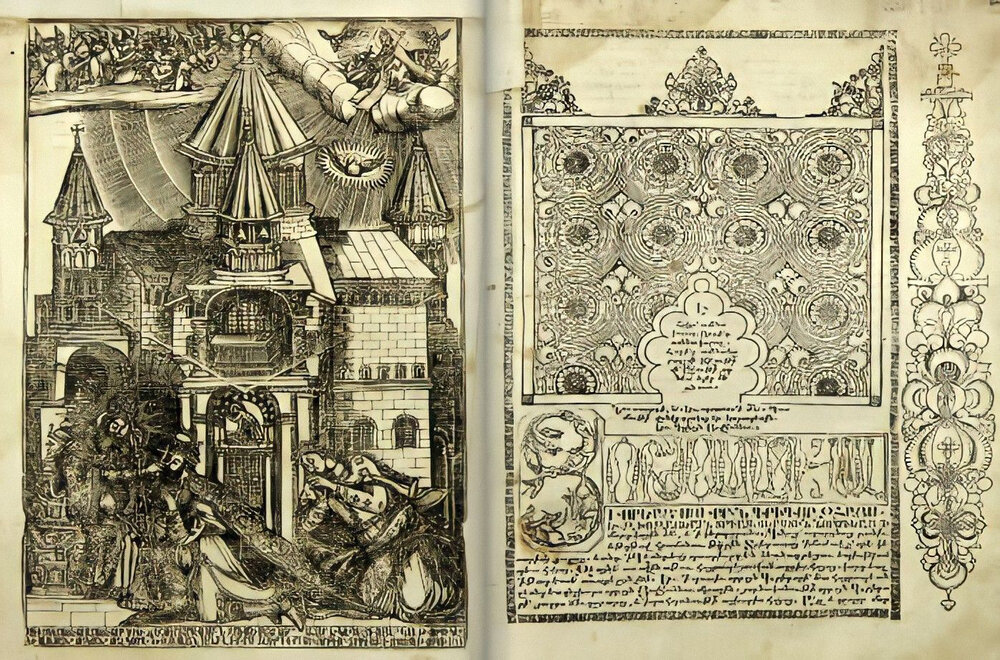

- [31] Mouradian, G. “Surb Kononos vanki oukhtagnacutyun” [Pilgrimage at the Monastery of Saint Kononos], in Byurakn, No. 31, September 17, 1898, p. 563.

- [32] Byurakn, No. 19-20, May 16, 1900.

- [33] Byurakn, No. 31 (1898), p. 562.

- [34] Mirakhorian, A Descriptive Journey to Armenian-populated Regions․․․, Vol. 1, p. 75.

- [35] Byurakn, No. 31 (1898), p. 563.

- [36] Teodik, The Calvary of Ottoman Armenian Clergy…, p. 131.

- [37] Mirakhorian, A Descriptive Journey to Armenian-populated Regions․․․, Vol. 1, p. 75.

- [38] Teodik, The Calvary of Ottoman Armenian Clergy…, p. 131.

- [39] Byurakn, No. 31 (1898), p. 563.

- [40] Mirakhorian, A Descriptive Journey to Armenian-populated Regions․․․, Vol. 1, p. 74.

- [41] Hakobyan et al., Dictionary of Toponymy of Armenia…, Vol. 3, p. 208.

- [42] Hakobyan et al., Dictionary of Toponymy of Armenia…, Vol. 1, p. 372.

- [43] Karapetyan, Samvel. Hayastani patmutyoun. Hayots dzor, hator A [A History of Armenia: Hayots Dzor], Vol. 1. Yerevan: Foundation of Research on Armenian Architecture, 2015.

- [44] Baghyan, Hovhannes. Hamarot storagrutyun Haykadzor yev Vostan gavarac [A Concise Description of Haykadzor and Vostan Counties]. Sion, 1869, No․ 11, p. 251.

- [45] Sauer, Eberhard W. Sasanian Persia: Between Rome and Steppes of Eurasia, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017, p. 192.

- [46] Petoyan, The Historico-geographical Topography of Sassoun…, p. 54.

- [47] Karapetyan, A History of Armenia: Hayots Dzor, Vol. 1.

- [48] Testimony of genocide survivor Armenak Amrikian, in Memorial Heritage, Vol. 14, The Foundation of Research on Armenian Architecture, Yerevan, 2011, p. 282.

- [49] Badalyan, A Historico-demographic Description of Western Armenia…, p. 39․

- [50] Badalyan, A Historico-demographic Description of Western Armenia…, p. 39․

- [51] Hovhannisyan, Karen. Toukh Manuk Avetarannere [The Gospels of Touhkh Manuk]. Yerevan: The Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography at the National Academy of Sciences of Armenia, 2019, p. 249.

- [52] Hakobyan et al., Dictionary of Toponymy of Armenia…, Vol. 1, p. 682.

- [53] Ghazaryan, Vazgen. “Tigranakert mayrakaghaki teghoroshman shourdj” (Reflections on the Localization of the Capital City of Tigranakert), in Armenia and Oriental Christian Civilization, Part II: Papers and Abstracts, Yerevan: Gitutiun Publishing House, 2017, p. 154.

- [54] Mirakhorian, A Descriptive Journey to Armenian-populated Regions…, Vol. 1, pp. 67-69.

- [55] Hakobyan et al, Dictionary of Toponymy…, Vol. 4, p. 444.

- [56] Badalyan, A Historico-demographic Description of Western Armenia…, p. 41.

- [57] Hakobyan et al., Dictionary of Toponymy of Armenia…, Vol. 3, p. 208.

- [58] Byurakn, No. 31 (1898), p. 562․

- [59] Statistical report prepared by the Sgherd Prelacy in 1902, sheet 10, No. 51 (Norshen).

- [60] Badalyan, A Historico-demographic Description of Western Armenia…, p. 30.

- [61] Mirakhorian, A Descriptive Journey to Armenian-populated Regions․․․, Vol. 1, p. 74.

- [62] Petoyan, The Historico-geographical Topography of Sassoun…, p. 54.

- [63] Karapetyan, A History of Armenia: Hayots Dzor, Vol. 1.

- [64] Mirakhorian, A Descriptive Journey to Armenian-populated Regions…, Vol. 1, pp. 143-144.

- [65] Petoyan, The Historico-geographical Topography of Sassoun…, p. 72.

- [66] Hakobyan et al., Dictionary of Toponymy of Armenia…, Vol. 3, p. 745.

- [67] See, for example, Martirosyan, Tigran. “Sassoun—Demography: Population Statistics per Village,” in Houshamadyan, https://www.houshamadyan.org/mapottomanempire/vilayet-of-bitlispaghesh/sassoun/locale/demography.html.

- [68] Mouradian, Mkrtich. “Hrecvari srbavayrere yev anhayt aghbyuri avandutiune” [Holy Sites of Hrecvar and the Tradition of an Unknown Spring-Well], Hayastani kochnak, No. 25 (1922), p. 818.

- [69] Petoyan, The Historico-geographical Topography of Sassoun…, p. 58.

- [70] Mouradian, Mkrtich. “Avandutiunner Sasno oukhtategheac masin” [Traditions of the Pilgrimage Sites of Sassoun], Hayastani kochnak, No. 7 (1922), p. 238.